This is the second of two posts on 20th-century Muslim heritage in Indianapolis that come to us from Millennium Chair of the Liberal Arts and Professor of Religious Studies at the Indiana University School of Liberal Arts at IUPUI, Edward E. Curtis IV. Click on Indianapolis’ Homegrown Islam: The Moorish Science Temple of America for the first post.

Mirzā Ghulām Ahmad (1835-1908), the founder of the Ahmadiyya Movement in Islam (click on image for expanded view).

In 1930, national Muslim missionary Sufi Bengalee came to visit the small, but growing community of Muslims in Indianapolis devoted to the teachings of a Punjabi religious leader named Ghulam Ahmad. Bengalee was the American missionary for the Ahmadiyya movement, which was one of the first modern, international Muslim movements to gain a significant number of converts among non-Muslim populations, especially in the West. The Ahmadiyya were a reform-minded group that emphasized the peaceful nature of Islam and eschewed polygyny. It was named after its founder, Ghulam Ahmad, whom many followers believed was the Messiah and the Mahdi, the rightly-guided figure in Islamic tradition who will appear on earth to preach justice before the Day of Judgment. Some followers also thought Ghulam Ahmad to be a prophet, a belief that was and is rejected by most of the world’s Muslims—whether Sunni or Shi‘a—who believe that Muhammad of Arabia (d. 632 CE) was God’s final prophet. But before Sunni or Shi‘a Muslims had established a congregation in Indianapolis, it was Ahmadi Muslims who were encouraging Hoosiers to convert—and doing so across Indianapolis’ stark color line.

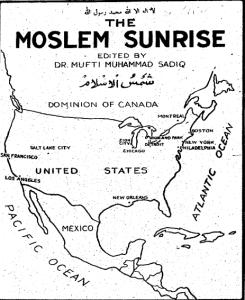

In 1921, the Ahmadiyya movement established its U.S. headquarters on Wabash Avenue in Chicago and began publishing the Moslem Sunrise newspaper. Soon after, the movement attracted its first Hoosier converts in Gary and other parts of northern Indiana. By 1923, Hoosiers were appearing on the pages of the Moslem Sunrise, and their names reveal that Hoosier women were as attracted to this movement as men were. Many of them took Muslim names after converting. In 1923, the Moslem Sunrise noted that Miss Laura B. Howard became Sister Aaminah; Miss Mary Lee Curtis became Sister Azeezah; and Miss Bettie Saunders became Sister Amatur Rehman.

In 1929 the Ahmadiyya mission had moved to 1846 Boulevard Place, just a couple doors north of the Alpha Home for Colored Women.

By 1926, according to the Indianapolis Recorder, the Ahmadiyya had a mission in Indianapolis. It was located at 1115 Fayette Street, which was occupied, according to the 1927 city directory, by one Koram Elihee. This was a small, shotgun house, situated behind the color line near what today is 10th Street and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard, south of Methodist Hospital. By 1929, Koram Elihee moved the mission to 1846 Boulevard Place, a duplex/split house which was located next door to the Alpha Home for Colored Women. Now spelled Karm Alahee, this leader was listed in the city directory as “mgr [manager], Ahmadia Moslem Mission.” In 1930, the same year that Sufi Bengalee decided to visit, at least 12 Muslim men and women in Indianapolis donated a total of $51–the equivalent of over $700 today–toward the publication of the movement newspaper.

Bengalee’s visit was important enough to attract the attention of both the Indianapolis Star and the Indianapolis Recorder. During his interviews with the Star, Bengalee emphasized the unique nature of Ghulam Ahmad: “We believe that Ahmad is the prophet of the age, and that he has brought Islam back to its original purity.” The article in the Recorder was the more critical one, emphasizing the differences between Christian and the Ahmadi Muslim teachings about Jesus. The article’s lead was, “That Christ did not die on the cross, but after his apparent death escaped and lived in old age in [the] northern part of India is the assertion of Dr. Sufi M. R. Bengalee.” The Recorder was referring to the Ahmadi belief, shared by many followers of metaphysical and esoteric groups, that Jesus had immigrated to India after the events that Christians commemorate as the Crucifixion and Easter. Bengalee also told the Recorder that believing in Islam “requires belief in the founders of all religions, including Christ, Moses, Buddha and Krishna whom he declares are common beneficiaries of mankind.” Though not a belief shared by most Muslims around the world, this assertion was not unusual within the world of metaphysical religions, including what would become known later as New Age religion. Such religious ideas were more popular in the 1920s among Americans, of various racial backgrounds, than one might imagine. But the Recorder, which favored a more traditional Christian understanding, would have none of it, declaring that “the divinity of Jesus Christ is attacked by the Islam leader, who admits, however, that the Saviour was a prophet.” The newspaper did appreciate the fact that Bengalee preached against racial discrimination, noting his opposition to public segregation.

The conversion story of Indianapolis resident Haze Hurd (Abdul Hameed) appeared in Moslem Sunrise in 1932.

Bengalee’s visit convinced at least one White Hoosier, and perhaps more, to convert to Islam. Born in 1876, Haze Hurd was an Indianapolis carpenter who came to believe in what he regarded as the religious truths that Bengalee was teaching. As Hurd wrote in the Moslem Sunrise in 1932, “the spiritual truths that he propounded in his engaging way went straight to my heart.” On December 12, 1931, Bengalee visited Hurd and some of his friends at Hurd’s Indianapolis home. “We discussed religion for four full hours and I was convinced of the Truth of Islam,” Hurd explained. Hurd liked the fact that in the Ahmadi interpretation of Islam, the founders of all world religions, including not only Judaism and Christianity but also Hinduism and Buddhism, were honored. “I found that Islam is the embodiment of all religions, purified of all the corruptions that have gathered into them,” he declared. The next day, on Dec. 13, Hurd went to the mission and officially embraced Islam.

Sufi Bengalee visited the city again in 1932. According to the Star, Bengalee conducted “a series of services on the religion of Islam. . . at 8 o’clock on Friday and Sunday nights in the Ahmadiyya Moslem Mission, 1419 Roosevelt Avenue.” The mission had now moved out of its manager’s house to the former site of the Emmanuel Baptist Church.

After World War II, the movement’s popularity among African American and White Hoosiers declined. Many Hoosier converts became Sunni Muslims, deciding to follow the majoritarian tradition in Islam, while others joined the Nation of Islam, the African American group led by Elijah Muhammad. Ahmadi Muslims remained in Indianapolis, but the majority of them today trace their ethnic roots to South Asia, the birthplace of the movement.

Reference

Haze Hurd (Abdul Hameed)

1932 Why I Became a Moslem. Moslem Sunrise 4(3):15-16.

Moslem Sunrise

1923 New Converts. Moslem Sunrise 2(1):169-171.

1930 Donors of the Moslem Sunrise. Moslem Sunrise 3(3):23.

Richard Brent Turner

2003 Islam in the African-American Experience. 2nd edition. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Images

Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (circa 1897) image from Wikipedia

Reblogged this on Edward E. Curtis IV.

LikeLike

Pingback: Ahmadiyya in Indianapolis – ahmadiyyafactcheckblog

Pingback: Ahmadiyya in Indianapolis – ahmadiyyafactcheckblog