In January, 1937 William Lane died in a hit-and-run accident in the 1000 block of North West Street (now known as Martin Luther King, Jr Street). The 56-year old Lane had returned to his home at 1044 North West Street before realizing he had forgotten to purchase pepper. Lane headed back out to the grocery and was returning with pepper in hand when a car hit him and killed Lane instantly.

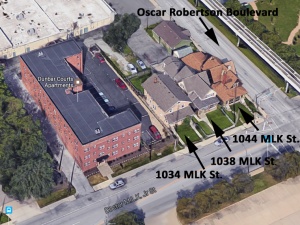

A 2016 Google image of the 1000 block of Martin Luther King Jr. Street (click for a larger view). The building on the left of the image is Dunbar Court Apartments, which opened in 1922 and erased three of the four building once on the west side of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Street, now known as North West Street.

Nobody who is familiar with this stretch of road today would be surprised at the lethality of that streetscape. The once-settled neighborhood is now a confluence of interstate off-ramps built in the 1960s that empty onto constantly re-engineered streets that struggle to accommodate busy traffic. Once part of a walkable neighborhood of homes, stores, churches, and schools, the 1000 block of MLK Street now seems designed simply to serve cars. Not much more than a dirt path in the mid-19th century, the block is now a mostly invisible space on the way to and from state government complexes, the Indiana University Medical Center, and IUPUI.

When William Lane died the neighborhood along MLK Street was a central but more modestly trafficked thoroughfare sitting just south of Crispus Attucks High School. William and Virginia Lane’s home still sits at the corner of North West and 11th Streets, now known as Martin Luther King Jr Street and Oscar Robertson Boulevard respectively. Many of the surrounding homes were removed by urban renewal projects and interstate construction that began after World War II, but the Lanes’ home has been spared in part because it is now part of the Ransom Place Conservation District. Yet few of the thousands of people driving by the house each day likely notice the homes that tenaciously hang on in the 1000 block of Martin Luther King, Jr. Street.

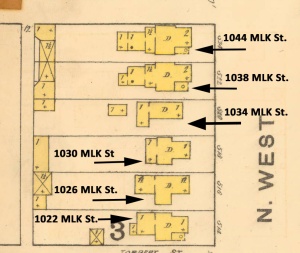

An 1887 Sanborn Insurance Company map shows the homes along North West Street (click for expanded view). Indianapolis house numbers have changed three times, and this map included the earliest house numbers (present-day numbering is added in black).

The home where William and Virginia Lane was living in 1937 was first occupied in 1876. The house was one of five neighboring homes between Torbert and 11th Streets all built and first occupied in 1876; a sixth was added by 1878. In 1876 Lawrence and Harriett Culloden moved into what became the Lanes’ house in 1933. Lawrence Culloden was born about 35 kilometers southwest of Dublin in Blessington, County Wicklow, Ireland in 1823. His family went to Canada in the late 1830s, apparently with nine siblings accompanying their parents. In January, 1839 Lawrence and his brother Andrew appeared in a British militia pay list, when the two teenagers were almost certainly part of the military forces responding to Canadian rebellions in 1837-1838. Lawrence was managing a grocery in Milton in 1857 (roughly halfway between Toronto and Hamilton), where he was married five years later to Harriett Platt. Platt was born in Canada, but her father and mother were born in New York and Connecticut respectively.

On April 25, 1871 the Indianapolis News ran this ad for Lawrence and Frederick Culloden’s grocery on Illinois Street (click for expanded view).

Lawrence and Harriett moved to Indianapolis with Harriett’s parents between February and May 1870. Lawrence’s younger brother Frederick had migrated from Canada to St. Louis in 1862, and he joined his brother in Indianapolis in 1870. The brothers opened a grocery on Illinois Street, but they abandoned the grocery business in January 1873 when Lawrence Culloden purchased a realty firm. Lawrence’s realty business was a partnership with his brother-in-law, Scottish immigrant William Gordon; Gordon’s wife Martha was Harriet Culloden’s sister, and the sisters’ mother Grace Platt lived with the two families in Indianapolis. The building permits for at least two of the North West Street homes’ construction were in Grace Platt’s name: in April 1875 Platt secured a building permit for $1800 to construct a dwelling on North West Street in what is now the 1000 block; a month later a building permit was again secured in Platt’s name for the same area for a structure valued at $2000. One of these almost certainly was the home the Cullodens moved into in 1876 with Grace Platt.

Both the Culloden and Gordon households secured some modest measure of affluence. For instance, in 1880 both the Cullodens and Gordons had live-in servants, which was relatively uncommon in the surrounding neighborhood. The Cullodens had a 13-year-old English woman doing their household labor, and the Gordons had a 21-year-old Canadian woman. Harriet Culloden died in November 1882, and Lawrence Culloden followed her to Crown Hill Cemetery in 1886. Grace Platt survived her daughter and lived on North West Street until 1895, when she moved back to Ontario to live with her son.

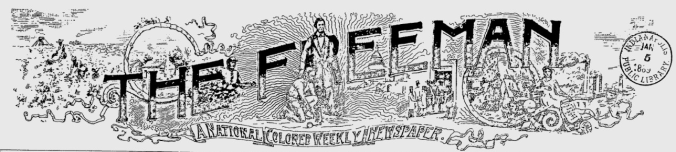

Moses Tucker’s newly designed masthead for The Freeman first appeared on the paper on January 5, 1889. In 1890 he was living with publisher Edward Cooper at the home that would now be 1030 Martin Luther King Street.

Ransom Place and the near-Westside are most closely associated with their predominately African-American population, but before 1910 only a modest number of African Americans lived in the homes along North West Street. They included Edward Cooper, who began publishing the African-American newspaper The Freeman in 1888. The Freeman was well-known for its lavish illustrations, and one of the newspaper’s engravers, Moses L. Tucker, was living with Cooper in 1890 at what would today be numbered 1030 North West (now razed). The Freeman’s stunning new masthead unveiled in December, 1889 was Tucker’s design and includes his signature hidden away in the design. In July, 1890 the Indianapolis News acknowledged that Tucker had “extraordinary gifts as a draughtsman,” but Cooper fired Tucker in 1892 because Tucker was struggling with mental illness (Cooper sold the paper in 1892). Tucker was committed in March 1892 and held in local facilities until 1899, when he became a patient at the newly opened Marion County Hospital for the Insane in Julietta (most of the facility still stands today just southeast of Indianapolis). He remained held there until his death in April, 1926, and with no surviving family to claim his body his remains were ceded to the state for medical testing. The Indianapolis News wrote a long article at Tucker’s death, but it indicated that “prior to his being admitted to the county infirmary several years before the Julieta [sic] institute was built, nothing is known of his history.”

Harry A. Brown appeared in an April 9, 1910 The Freeman article detailing his show with his sister Lulu.

Public school teacher Landonia Williams was the sole African-American resident in the 1000 block in 1900. Ten years later, though, the census-keeper found that every household in the 1000 block was African American. Several of the households that subsequently lived in the block were linked to the city’s rich African-American musical tradition. In 1910, the house now numbered 1042-1044 Martin Luther King Street was home to Charles W. and Sally Brown’s family, and three children (and one daughter-in-law) all appeared in the census as performers in “comic opera.” Siblings Harry, Frank, and Lulu sang, played, performed, and managed some of the nation’s best-known African-American theatrical and minstrel troupes. These African-American troupes mixed a variety of theatrical performance, music, and dance for both White and Black audiences. In 1899 oldest sibling Harry A. Brown performed with the Smart and Williams Troubadours, and by 1903 he was stage manager, play writer, and performer in the variety tent troupe Coontown 400. Brown’s wife Catherine was a singer in the Coontown 400 troupe, which had begun under White management in 1899, and in 1904 it became Harry Brown’s Coontown 400.

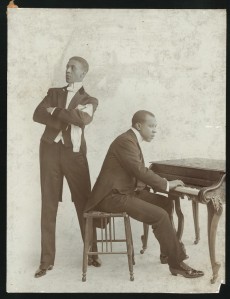

Frank Brown performed with Bob Cole (left) and J. Rosamond Johnson (right), shown here in a circa 1898-1910 publicity photo. Cole and Johnson were among the best-known performers in turn of the century African-American musical theatre.

Such African-American musical theater was known as “coon shows,” which today would be an unacceptable racist term, and African-American performers sometimes lapsed into the racial caricatures associated with Blackface minstrelsy. Nevertheless, many of these shows introduced American society to African Americans performing ragtime and blues music, dance, theatre, and humor. Beyond transforming American popular culture, these performers entertained countless Americans, and the emergence of such entertainment employed many African-American performers and fueled the growth of a massive Black entertainment industry. Indianapolis’ The Freeman covered African-American musical theatre as closely as any periodical in the country, and companies seeking out African-American talent routinely ran ads in The Freeman. Many of the musicians associated with ragtime, cake walks, and associated traditions lived in Indianapolis and performed in the theaters along Indiana Avenue.

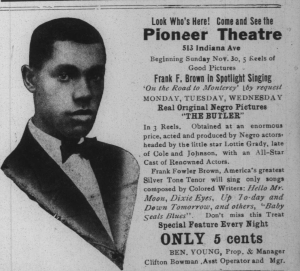

A November, 1913 advertisement in The Recorder featured Frank Fowler Brown at Indianapolis’ newly opened Pioneer Theatre (click for an expanded view).

Henry’s younger brother Frank Fowler Brown graduated from Indianapolis High School (now Shortridge) in 1899, and he appeared as a musician in the 1900 census and toured with Harry. Frank toured in 1908 and 1909 with J. Rosamond Johnson and Robert Allen Cole’s operetta “The Red Moon.” The work reflectively examined African-American and Native American relationships, moving many White critics to dismiss the play for breaking from Black and Indian stereotypes alike. In April, 1910 Frank and sister Lulu Brown played Indianapolis’ Colonial Theater “clad in Indian costumes” and singing “Indian songs.” Frank went on to perform with the well-known “Black Patti Troubadours,” a troupe featuring African-American opera singer Sissieretta Jones. Frank’s credits also included appearances with Noble Sissle, Al Jolson, and Indianapolis musician Ben Holliman. Like many African-American performers, Frank Brown had received much of his musical training in church. He eventually became the Choir Director of Indianapolis’ well-known Bethel AME Church while working at Diamond Manufacturing Company until his death in 1943.

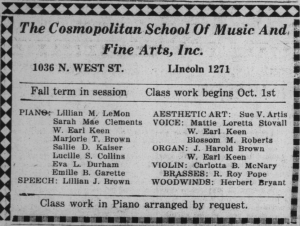

Another neighborhood musical institution opened in 1926, when the Cosmopolitan School of Music and Fine Arts opened at 1036 North West Street. The director of the school, Lillian Morris LeMon, was born in Chicago in 1894 and was living in Louisville with father William and mother Ada in 1900. Like many African Americans, the Morrises went north in the early 20th century, arriving in Indianapolis by 1902. Lillian married Philippine immigrant Angel LeMon in 1913, and in 1920 Lillian and Angel were living at 1128 North Senate Street with two Philippine-born migrants who were all working in Angel’s restaurant at the same address (now under Interstate 65). Angel was born in Guindulman, Bohol in about 1888 and came to Indianapolis around 1903, but there would never be a sizable Philippine-born community in the Circle City: in the 1920 census, for instance, Angel was one of only seven Indianapolis residents born in the Philippines.

The Lemons moved to North West Street just before Lillian opened her music school just one year before the segregated Crispus Attucks High School opened a block away. In October, 1926 The Recorder indicated that LeMon’s school had two grand pianos, and the studios “have been furnished with taste and have a very Artistic atmosphere.” Lillian trained with a rich range of instrumental and voice instructors, including Oscar Willard Pierce in his College of Musical Art as well as Indiana University lecturer John L. Geiger. Lillian’s friend Lucretia Lawson Mitchell (later Lucretia Love) attended Fisk Academy and was trained in Europe, performing as a soprano throughout the US and Europe (e.g., in 1933 she sang in Galveston Texas). Lucretia’s brother Raymond Augustus Lawson also was a noted pianist who toured Europe and spent 60 years giving piano lessons to students in Hartford, Connecticut.

Many Indianapolis musicians taught in Lillian LeMon’s school, including the performers in this September, 1930 ad (click for expanded view).

Lillian’s neighbor Virginia Cleveland Lane taught in LeMon’s school after she moved to North West Street in 1933, and she lived in the home until her death in 1968. Virginia Cleveland was a graduate of West Virginia Collegiate Institute (now West Virginia State), and she married William Lane in Staunton, Virginia in 1912 and moved to Indianapolis. She and Lillian were active in the Indiana State Association of Negro Musicians and the Indianapolis Music Promoters. Lane’s husband died in the January, 1937 hit-and-run on North West Street, and in September she re-wed, marrying Henry Fleming (as with her first marriage, the wedding was held in Staunton, Virginia). Henry Fleming was a caddy at the Indianapolis Country Club after it expanded to a nine-hole course in 1897, a course that is today the grounds of the Woodstock Country Club. In 1901 he became the first golfing instructor at the city’s new Riverside Park, but golf courses and other public leisure spaces were rapidly segregated in the first decade of the 20th century, and Fleming was fired at Riverside in 1902. Fleming was active in local politics for a half century, first for the Republican party and then going over to the Democratic party during the Depression. His wife worked at the Phyllis Wheatley YWCA and Flanner House and managed an African-American book club as part of her busy social life. After Henry’s death in 1964 Virginia continued to live on North West Street until her death in 1968.

A central goal of Invisible Indianapolis is to illuminate these rich stories that often pass without notice. The corner of MLK and Oscar Robertson Boulevard is today experienced by most people as an anonymous point on daily trips to and from work, school, or business downtown. This is perhaps understandable, but the challenge is that places that can be ignored become ripe for decline and displacement themselves. One of our goals is to draw attention to places like the 1000 block of Martin Luther King, Jr. Street that seem “hidden” in our midst and emphasize the interesting stories and fascinating people who have lived in the city.

Sources

Lynn Abbot and Doug Seroff

2007 Ragged but Right: Black Traveling Shows, “Coon Songs,” and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz. University Press of Mississippi, Jackson.

Fitzhugh Brundage (editor)

2011 Beyond Blackface: African Americans and the Creation of American Popular Culture, 1890-1930. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

David Krasner

1997 Resistance, Parody and Double Consciousness in African American Theatre, 1895- 1910. St. Martin’s Press, New York.

Marvin Edward McAllister

2011 Whiting Up: Whiteface Minstrels and Stage Europeans in African American Performance. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

Bernard L. Peterson

1997 The African-American Theatre Directory, 1816-1960. Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut.

Paula Marie Seniors

2008 Cole and Johnson’s “The Red Moon,” 1908-1910: Reimagining African American and Native American Female Education at Hampton Institute. The Journal of African American History 93(1):21–35. (subscription access)

David Leander Williams

2014 Indianapolis Jazz: The Masters, Legends and Legacy of Indiana Avenue. The History Press, Charleston, South Carolina.

Images

Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson (circa 1898-1910) publicity image from Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library.

Have you included any information about the Historic Flanner House Homes located south of 16th street, north of Oscar Robertson? I would love to learn more about this area before the 1950’s as well as when the Flanner House Homes were built.

LikeLike

Try this https://paulmullins.wordpress.com/2013/05/07/race-and-suburban-homogeneity-the-flanner-house-homes-and-post-urban-african-america/

LikeLike