In 1958, eight of the graduates of the Indiana University School of Medicine’s first graduating class posed for this image. Clarence Lucas Sr. is s

2nd from the right in the front row (image IUPUI Special Collections, click for larger image).

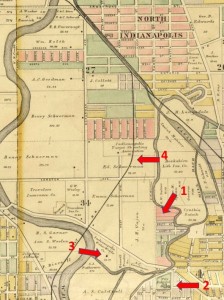

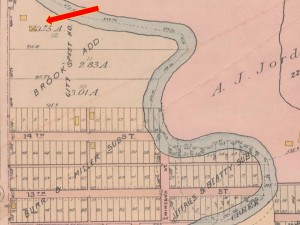

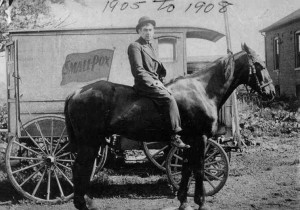

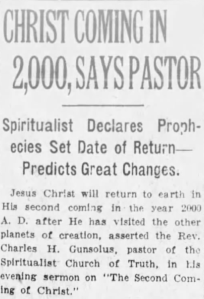

In May 1908 the Indiana University School of Medicine graduated its first class, and the graduates included Clarence Augustus Lucas. Lucas had come to Indianapolis in 1904 to study at the Central College of Physicians and Surgeons before he completed three years at the Medical College of Indiana, a Purdue University-affiliated medical school that was absorbed by Indiana University in April 1908. Lucas graduated in May 1908 and is today considered the first African-American graduate of the Indiana University School of Medicine. There is certainly reason for Indiana University to take pride in their alumnus, and there is much to celebrate about Lucas’ service to the community and his career in the face of anti-Black racism. Nevertheless, his history is punctuated by persistent structural racism and personal dehumanization that illuminates the ways racism has been embedded in medical training and African-American health care since Emancipation. Clarence Lucas’ story is not simply a historical artifact; instead, it is consequential today because the heritage of race, medical training, and public health care in Indianapolis profoundly shapes contemporary experiences of health care across the color line.

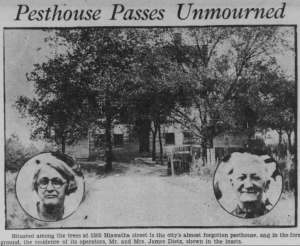

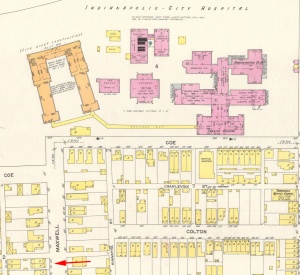

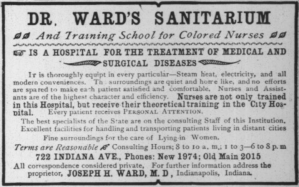

In October 1910 this ad for Joseph H. Ward’s Sanitarium and Nurses Training School appeared in the Indianapolis Recorder (click for larger image).

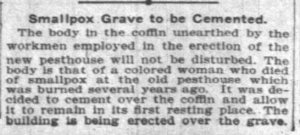

Most African Americans’ medical care that would today warrant hospitalization was administered at home well into the 20th century. Family members, midwives, alternative medicine practitioners, and root doctors treated African Americans alongside a small circle of licensed medical doctors; in 1923, for instance, The Indianapolis Colored Directory and Year Book identified 15 physicians serving more than 34,000 African-American residents. Indianapolis’ City Hospital admitted Black patients and reserved a modest number of beds for African-American patients, but no African-American physicians could attend patients in the hospital. There were several small African-American hospitals, but they had perhaps 50 beds between them. Joseph Ward graduated from the city’s Physio-Medical College in 1897 and then completed a degree at the Medical College of Indiana in 1900, and he was admitting patients to his private Ward’s Sanitarium hospital by August 1906 (perhaps as early as 1905). An August 1909 description of the Sanitarium attached to Ward’s home indicated that it had 16 beds. In March 1912 Ward announced his plan to merge his hospital with the Sisters of Charity Hospital. Planning for the Sisters of Charity Hospital began in October 1909, a lot was purchased at Missouri and 15th Streets a year later, and the hospital opened there in June 1911. The third hospital for African Americans was Lincoln Hospital, which was established in 1909 by a group of African-American physicians whose Board of Managers included Clarence Lucas. The 20-bed hospital at 1101 North Senate could accommodate 17 patients, and its surgery had been outfitted with funding from Indianapolis Motor Speedway co-founder Carl G. Fisher. Nevertheless, the hospital would close in 1915. The three modest hospitals could hardly address the medical care for a rapidly expanding African-American community.

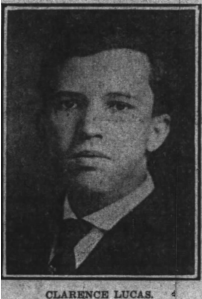

In June 1910 the Indianapolis News‘ pictures of the six City Hospital interns included Clarence A. Lucas.

Clarence Lucas was born in Huntington, West Virginia in November 1884 and was probably living in Piketon, Ohio in the late 1880s. The 1900 census recorded him living in Piketon with his mother Anne’s parents Abraham and Mary Jackson (when Clarence graduated in 1908 most newspapers indicated his home was Piketon). Lucas likely arrived in Indianapolis for his medical training in 1904, and in 1905 he was living at 427 West Vermont Street. In May 1908 Lucas graduated, and shortly afterward he was part of a group of recently graduated physicians tested to assume six interne positions at Indianapolis’ City Hospital. On June 1st the Indianapolis News confirmed that Lucas had secured one of the positions, reporting that “Much interest of an unusual nature attaches to the list of City Hospital internes, as it includes the name of a negro, Dr. Clarence Lucas. Dr. Lucas took sixth place in the competitive examination.”

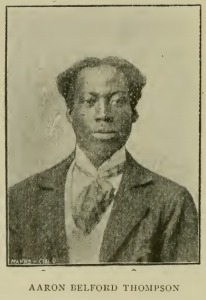

Sumner Furniss became the first African-American interne in Jun 1894, when this image appeared in the Indianapolis News.

Lucas became just the second African-American interne at City Hospital, following Sumner Furniss in 1894. When Furniss reported to City Hospital in June 1894 the Hospital Superintendent reported that four patients “had already entered their objections to being attended by a colored physician.” Yet several prominent White physicians insisted Furniss was qualified and should assume his interne position, and the Indianapolis Journal editorialized that the “time has passed when an educated colored man who shows qualifications of a high order can be set aside for public duties because negro blood courses his veins. If there are men or women in the hospital who feel that they cannot serve with Dr. Furniss because his skin is a little darker than theirs, they can resign.”

In 1911 Lawrence Aldridge Lewis topped the exams for City Hospital internes (Indianapolis Star 16 April 1911).

Despite such seemingly progressive sentiments, racial segregation increased in the early 20th century, and just four African-American physicians interned at City Hospital between Lucas’ appointment and 1917. Lawrence Aldridge Lewis entered the IU School of Medicine in 1907, graduated in the class of 1911, and became an interne in April 1911. Lewis practiced in Indianapolis until his death in 1964. The other three had long medical careers but did not work in the Circle City. Albert Buford Cleage, for instance, graduated from the IUSM and became a City Hospital interne in 1910 before moving to Michigan in 1914. Howard Randall Thompson graduated from IUSM in June 1913, became a City Hospital intern, and returned to practice in Evansville in 1914, where he died in 1929. After his entrance exams, William Walden Gibbs was selected as a City Hospital interne in 1917, but he was required to agree to eat with other Black employees in a segregated dining space “and to treat only those colored patients who might be assigned to him.” Gibbs initially accepted those terms, but the White interns served notice at the beginning of June that they refused to work alongside Gibbs, and on June 15th the White physicians walked out. Gibbs resigned and a week later the NAACP met to petition for Gibbs’ reinstatement. A group of African Americans met with the Board of Health, but Gibbs abandoned the effort and moved to Chicago in 1919, and he eventually became Joe Louis’ family physician; Gibbs died in February 1948.

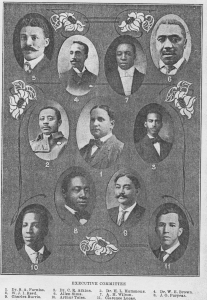

In 1910 more than half of Indianapolis’ African-American M.D.s were part of the Lincoln Hospital Executive Committee, including Clarence Lucas Sr.

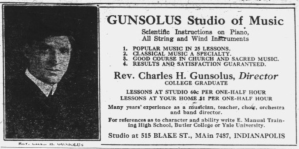

Clarence Lucas established a private practice after his City Hospital internship, and in his family’s hands the practice would continue in the city’s near-Westside into the 1990s. In 1910 Lincoln Hospital counted Lucas among the city’s 19 African-American physicians, nearly all of whom had been trained in a legion of proprietary medical schools in the late 19th century and the first decade of the 20th century. The city’s earliest African-American physician, Samuel A. Elbert, was born free in Maryland in 1832 and came to Indianapolis after the Civil War. He graduated from the Indiana Medical College in 1871 and died in July 1902. Sumner Alexander Furniss established his practice in 1895 after becoming City Hospital’s first African-American interne in 1894, and he would become Indianapolis’ first African-American City Councilman in 1917. Born in Mississippi in 1874, Furniss and his parents moved to Indianapolis in about 1883, where his father William was a public school teacher. Sumner received his medical degree from the Medical College of Indiana in 1894 and continued to practice in the city until his death in 1953. His brother Henry Watson Furniss finished his medical training as well as a pharmaceutical degree at Howard University in 1895. In 1898 he became the US consul in Bahia, Brazil and in 1905 he became the Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Haiti (that is, the US Chief of Mission), serving until 1913. Born in North Carolina in 1872, Joseph Henry Ward finished his medical training in Indianapolis at the Physio-Medical School of Indiana.

Aspiring African-American medical students had increasingly fewer options for training in the 20th century. In 1910 the Carnegie Foundation’s enormously influential study Medical Education in the United States and Canada ensured the segregation of medical training and a paucity of Black physicians for a century. Known as the Flexner Report, author Abraham Flexner was enlisted to professionalize medical training, visiting all 155 medical schools in operation in 1909. Flexner advocated reducing those 155 schools to just 31 institutions, and he championed the elimination of all but two African-American medical schools: that decree would leave just Howard University Medical School and Meharry Medical College as institutions training a significant number of Black medical professionals. Those two institutions trained three-quarters of the nation’s Black doctors in the subsequent half-century. The Flexner Report assumed Black physicians would exclusively treat Black patients in a segregated society, and Flexner voiced a commonplace White wariness of the public health dangers posed by African Americans, arguing that “The practice of the negro physician will be limited to his own race, which in its turn will be cared for better by good negro physicians than by poor white ones. But the physical well-being of the negro is not only of moment to the negro himself. Ten million of them live in close contact with 60 million whites. …. The negro must be educated not only for his sake, but for ours. He is, as far as human eye can see, a permanent factor in the nation. He has his rights and due and value as an individual; but he has, besides, the tremendous importance that belongs to a potential source of infection and contagion.” The segregation of medical schools and interne opportunities ensured a very modest number of African-American physicians into the 21st century.

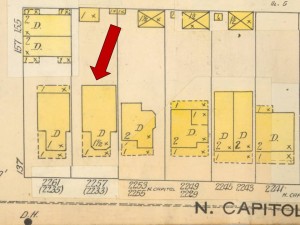

Clarence Lucas married teacher Carrie Heston in June 1912, and they were living at 2008 Bellefontaine Street in July 1913 when their daughter Carolyn Heston Lucas was born and son Clarence Lucas Jr followed in December 1914. The family was living there in April 1930 when the census recorded the neighborhood’s demography and identified the Lucases as the only Black family in the immediate area. In December the family purchased a home at 3934 Central Avenue, “in the heart of what is known as Indianapolis’ well-to-do district,” which was an exclusively White neighborhood. Lucas bought the home from White physician Clark E. Orders, and the Indianapolis Recorder suggested without explanation that “Dr. Orders sold the home to `spite’ the neighborhood.” A week after moving into the home, the Central Avenue neighbors met and formed the Northside Protective Association, one of a series of inter-war Indianapolis neighborhood collectives lobbying against residential integration. The exclusively White neighborhood group on Central Avenue “unanimously decided at the meeting that should Dr. Lucas and the latter’s family persist in living in their recently purchased home, the league would see to it that ever Negro employed in domestic service within the district is discharged forthwith.” A committee of the White neighbors including Indianapolis Real Estate Board President and future Indiana House of Representative member Thomas E. Grinslade met with Lucas at his North West Street office. The Lucas family surrendered their Central Avenue home and returned to their former residence on Bellefontaine Street, where they remained until moving to East Riverside Drive in about 1953.

In 1989 the 75-year-old Carolyn Lucas Dickson was still practicing when the Indianapolis Star reported on the practice.

Both of Clarence and Carrie’s children became physicians. Daughter Carolyn Lucas married in 1938 and completed her medical degree at Howard University in 1939. In about 1947 she began to practice alongside her father at 501 North West Street, almost certainly the first African-American female MD in Indianapolis. She practiced into the 1990s and died in September 2010. Like his father, Clarence Lucas Jr. was an Indiana University School of Medicine student who graduated in June 1940. In the 22 years after William Gibbs’ 1917 interne appointment ended, no African-American physician had interned at City Hospital. In August 1930, White physician and 1928 interne John Albert Egan voiced a commonplace resistance to integration when he told the Indianapolis Star that “The City hospital, in my opinion, is the greatest single blessing the colored population of Indianapolis enjoy. … I think every white or colored reader will agree that the maintenance of a nursing staff would be impossible at the hospital if colored doctors were admitted. Nurses would not train and work with them.”

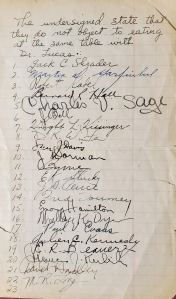

When City Hospital tried to enforce racial segregation of Clarence Lucas, Jr., 22 of his fellow internes wrote that they “do not object to eating at the same table with Dr. Lucas.” Nevertheless, hospital administrators and the Mayor ended Lucas’ interne appointment, and he completed his internship at Homer Phillips Hospital in St Louis (courtesy Lynn Lucas-Fehm).

Despite such sentiments, Clarence Lucas Jr. became the next City Hospital interne in November 1939. In July 1940, though, Lucas was dismissed after “he refused to eat in a dining room set aside for Negro internes.” Lucas told the Indianapolis Star that “`I am not interested in dining with white persons or having them dine with me. … But I do object to being subjected to indignities other internes do not have to suffer. I expected that certain phases of the medical services at the hospital would be closed to me but I did not expect that kind of discrimination.’” Twenty-two of Lucas’ fellow internes signed a petition that they did not object to dining with Lucas, but in August Mayor Reginald Sullivan upheld the dismissal of Lucas, concluding that “`There’s been a lot of friction between Dr. Lucas and the other internes all along.’” When African-American hospital orderly William Powell advocated for Lucas, Powell was also fired and accused of “creating disorder.”

In an interesting wrinkle, Clarence Lucas Sr. may not have been the only African-American graduate of the Indiana School of Medicine in 1908. In her 2016 study African-American Hospitals and Health Care in Early Twentieth Century Indianapolis, Indiana, 1894-1917, Norma B. Erickson recognized that Lucas’ fellow graduates included Alfred Hudson Hendricks. The vast majority of primary documentary evidence indicates Hendricks was African American. Hendricks was born in Georgia in 1882 and identified in the 1900 census as Black, and when Alfred and his wife Hazel had a son in 1908 the Indiana birth certificate identified the parents as Colored. Hazel’s father Henry Hart was a well-known African-American musician, and Alfred Hendricks’ office in 1910 was in the heart of the African-American community in the 1200 block of North West Street (now Martin Luther King Jr. Street). Alfred and Hazel divorced between 1920 and 1925, and when Hazel died in an auto accident in 1935, the death certificate identified her as Colored (IPS School 37 was named after the former teacher and Principal before closing in 2009). Nevertheless, in 1910 the census recorded Alfred Hendricks as White, as did his 1967 death certificate, the 1940 census, and his 1917 World War One draft registration. Those inconsistencies suggest Alfred Hendricks simply was perceived by some primary record keepers as mixed race or even White. He almost certainly deserves some recognition as sharing the status as one of the first African-American graduates of the IU School of Medicine.

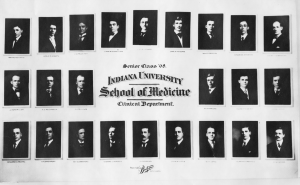

In 1908 the newly created Indiana University School of Medicine took this picture of 24 members of its first graduating class.

Like many other universities, the Medical School photographed its graduates in 1908, the first of over 100 graduating classes in the Indiana University School of Medicine. The Indiana University register of graduates identified 70 students who were awarded a 1908 IU Medical Degree, but only 24 students grace the class photograph. The graduating class image of the “clinical department” may have excluded students who had not received their full clinical coursework in the Indianapolis clinical training. Neither Lucas nor Hendricks appeared in the image, and that may be because some of their training was not at IU. Nevertheless, like many universities the Indiana University historical narrative that celebrates Lucas (and does not recognize Hendricks) tends to evade the ways racism in medical schools shaped African-American health into the 21st century. Contemporary community attitudes toward public health, the Medical School, and the city’s medical facilities are all shaped by that heritage, and serving the community today requires acknowledging that deep-seated histories of anti-Black racism inevitably shape present-day experiences of health care. Recognizing this history acknowledges institutional complicity in racism and admits that heritage shapes contemporary experience.

References

Carolyn M. Brady

1996 Indianapolis at the Time of the Great Migration, 1900-1920. Black History News and Notes 65.

Walter J. Daly

2002 The Origins of President Bryan’s Medical School. Indiana Magazine of History

98 (4): 265-284. (subscription access)

Norma B. Erickson

2016 African-American Hospitals and Health Care in Early Twentieth Century Indianapolis, Indiana, 1894-1917. Master’s Thesis, Department of History Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis.

Murray N. Hadley

1931 Medical Educational Institutions in Indiana. Indiana Magazine of History 27 (4): 307-315. (subscription access)

Louis W. Sullivan and Ilana Suez Mittman

2010 The State of Diversity in the Health Professions a Century After Flexner. Academic Medicine 85 (2): 246-253.

Images

1958 Indiana University School of Medicine Alumni image from IUPUI Special Collections and Archives.