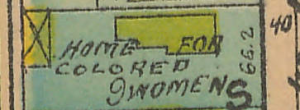

An 1892 Indianapolis News image of the Alpha Home for Aged Color Women, when it was located on Darwin Street.

In May, 1887 an Indianapolis News reporter toured the Alpha Home for Aged Colored Women, which had opened a year earlier in a home on Darwin Street “for the purpose of providing a home for indigent and aged colored women.” The Alpha Home was among a host of Progressive social service institutions that emerged in late-19th century communities to serve impoverished families, parentless children, and destitute elders. The most vulnerable new Hoosiers after the Civil War included African-American elders who often were unable to work, had no surviving family, and lacked any medical care at all. Unlike many of its peer social agencies run by churches, hospitals, social groups, and in some cases the state, Alpha Home was founded and long managed by African-American women to care for their most elderly neighbors who had survived captivity, and Alpha Home’s residents provide a unique voice for more than a century of African-American life.

In July, 1886 the Indianapolis News reported on the opening of the Alpha Home (click for an expanded view).

The new Alpha Home care facility was dedicated July 6, 1886, “in Fletcher’s Oak Hill addition, and the house, which Mrs. Merritt had built, will accommodate seven or eight persons and is well arranged.” The home on Darwin Street was donated by Paulina McClung Merritt, whose husband George managed the George Merritt and Company wool mill. The New York-born Quaker was closely linked to post-war philanthropy in the Circle City: after the Civil War, Merritt improved the former muster grounds now known as Military Park, he served on the Indiana Sanitary Commission, and he was instrumental in the establishment of the State Soldiers’ Orphans’ Home in Knightstown, Indiana.

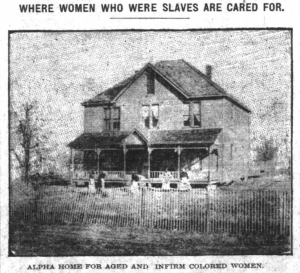

In March, 1900 this image of the Alpha Home facility on Darwin Street appeared in the Indianapolis News.

Merritt’s wife was an active philanthropist as well. She apparently was enlisted to support the Alpha Home cause by Eliza Goff, a former captive who was “for years a servant of Mrs. Merritt, the donor of the home.” Goff formed the initial Alpha Home association in 1879, and “after many years of discouragement” Merritt purchased a lot and contributed the new building in 1886. A year after it opened the Indianapolis News reporter waxed poetic about the home, indicating that the “place is so located as to catch all the sunshine, and has a pleasant, home-like appearance. On either side of the walk leading to the door are flower beds, and the yard is clean and well kept. … The room was neatly carpeted and famished. Over the mantel hung a steel engraving of Abraham Lincoln and a likeness of General Grant in colors.”

Like Goff herself, nearly all of the Alpha Home’s residents were former captives. In January, 1938 Robert Howard sat down for an interview with the Federal Writer’s Project at Alpha Home, one of many residents who bore witness to enslavement, several wars, and Jim Crow racism. Fifty years before Howard’s WPA Slave Narratives interview, two of the home’s very first residents retold their own stories of captivity. In May 1887 the sole “inmates” (the period term for residents) were Kaziah Pierce and Lucy Lane. Pierce (appearing in various records as Kizari, Keziah, or Kezey) gave her age in 1887 as 116, and when she died at Alpha Home in August, 1895 the Indianapolis News suggested she was 125 years old. In 1887 Pierce acknowledged that she was not certain when she was born, but she “remembered that she was five years old when her master’s son went off to a war, which she thought had a vague something to do with New Orleans.” If the reference was to the War of 1812 that would suggest she was born around 1807, but she might possibly have remembered the Cherokee-American Wars, since soldiers from her home in Kentucky fought in New Orleans in the late 1780s and early 1790s.

In either case, Pierce was a captive for at least five decades, and she spent most of that time held in Christian County, Kentucky. Pierce was apparently being held at Emancipation by Mary Gilmore Webb, whose father gifted Keziah to Mary and husband Bryant Webb. In 1860, the Bryants were living in Henry County, Kentucky and owned 11 captives, including one Black woman whose age was given as 50 and may well have been Kaziah Pierce.

Alpha Home’s numerous fund-raisers included yearly picnics like this one advertised in the Indianapolis Recorder in August, 1913.

Kaziah came to Indianapolis immediately after the war with two adult daughters and a son. She apparently met Solomon soon afterward, who she would describe as “probably” Keziah’s fourth husband; she told the Indianapolis News in 1887 that she had been “married three or four times, she is not sure which.” In 1892 Pierce indicated that her third husband had escaped captivity in about 1850, fleeing to Canada. By 1870 Solomon and Kaziah were living in Indianapolis, when Solomon appeared in the census as a blind wood cutter. Solomon was identified as blind (albeit unable to work) in the 1880 census, and when he died in 1882 he was about 96 years old. Pierce perhaps had as many as 20 children, though only three remained alive in 1887.

Kaziah became one of Alpha Home’s first residents in October, 1886. When Pierce died in August, 1895 the Indianapolis Journal suggested she was 133 years old (adding the odd note that “She had no memory of historical persons or events”); one death notice suggested she was 127; and the Indianapolis News somewhat more conservatively placed her age at death as 125.

In 1887 the Indianapolis News reporter indicated that Kaziah’s fellow-inmate, Lucy Lane, “has seen nature awaken from 106 winters.” Lane entered Alpha Home in August, 1886, but she had only lived in Indianapolis for about six years and did not appear in an Indianapolis City Directory until 1883. Lane indicated that she was “born in Virginia on the plantation of Nicholas Sowers,” who moved her to Kentucky when she was a child and whose family held her until Emancipation. Sowers held her grandmother captive as well, and “While in slavery three children were born to her, but all were taken away when young, and she knows nothing at all about them.” Lane died in May, 1891.

The Home typically had between five and 20 residents through World War II, and the privately held non-profit association was under constant pressure to raise funds from churches, local businesses, and a host of social organizations like the Major Taylor Bicycling Club. The modest frame building on Darwin Street was adjoining busy rail lines and the massive Atlas Engine Works, and in April, 1910 the Alpha Home caught fire, receiving significant damage to the structure. The building was repaired, but the structure’s decline and the stream of destitute residents that could not be accommodated fueled the Alpha Home Association’s interest in moving to a new facility. In February, 1914 Alpha Home moved to that new location at 1810 North Boulevard (sometimes referred to as North Senate Street), which was in the predominately African-American near-Westside. It also sat within blocks of other city service institutions including the Indianapolis Home for Aged Women (incorporated in 1867), the Altenheim German Home for the Aged, the Home for Friendless Colored Children, and the Marion County Workhouse.

In December, 1915, perhaps the Alpha Home’s most famous benefactor, Madam CJ Walker, was preparing to move from Indianapolis to Harlem, but the Indianapolis Recorder reported that it “is Madam Walker’s desire to see the entire Indebtedness paid on Alpha Home before leaving the city. With the assistance of the Board of Managers, she is making an effort to have this entertainment the biggest affair ever given in Indianapolis. … Madam Walker will give her famous Western Lecture, `The Negro Woman in Business,’ accompanied with stereopticon views of her business and property holding, which inspired and electrified thousands in the West and Northwest to higher aims and greater efforts. We feel it will be interesting to the people of Indianapolis, for while she lives here among them, there are but very few who know the magnitude of her business which is the result of but ten years labor.” Walker’s will left Alpha Home $1000 in 1919.

Madam CJ Walker’s 1919 will made contributions to many of her most important causes, including the Alpha Home.

In 1920 the federal census found 14 residents and a matron in Alpha Home (there had been 12 residents on Darwin Street a decade earlier). In 1923 the Indiana Board of State Charities visited Alpha Home’s 1840 Boulevard Place location and reported that the home “had 15 inmates, ranging in age from 65 to more than 100 years. The home is badly crowded. It is as clean and neat as can be expected under present conditions. Many things are needed. The home needs assistance badly.” Six years later the Fire Marshall recommended sweeping changes, suggesting that “the old Alpha home be torn down and replaced with a new fire proof building.

The Alpha Home admitted its first male resident in 1926 when Joseph Smiley became a resident. In 1930 the federal census found 19 residents in Alpha Home, including 64-year old Anthony T. Bradley, who was living in the home with his wife Jennie. Born in Carlton County, Kentucky in about 1861, Jennie Mitchell was living with Anthony on East Arch Street in 1910 (a location where she had been living by 1904, today just north of the Riley Towers). Both had survived the death of at least one spouse by 1910. Mitchell and Bradley were married in December, 1927. Anthony Bradley died in August, 1930, and Jennie Bradley died in May, 1936.

In 1938 Alpha Home resident Robert Howard became one of 21 Indianapolis residents interviewed by the Federal Writer’s Project. Like Parthenia Rollins a month earlier, Howard was interviewed by Anna Pritchett, the only African-American interviewer in Indiana. Pritchett’s interviews included a few rare quotes, but her interview of Howard resulted in an especially brief two-page biographical description of his time in captivity and the suggestion that “His master … was very kind to him.”

Nevertheless, Howard left a relatively rich documentary trail for the 70-plus years he survived after captivity. Howard was born May 6, 1855 on a slaveholding in Worthville, Kentucky, a small Carroll County community about 50 miles from Louisville. Howard remembered in 1938 that five Howard children lived with their mother Catherine on a separate slaveholding from their father Beverly, and after the war their father Beverly joined Catherine Howard and their children in Worthville.

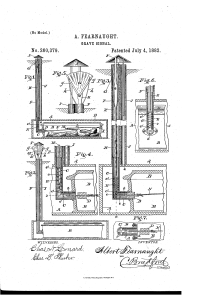

Robert Howard was working for photographer Albert Fearnaught in about 1882, the same year that Fearnaught patented this safety coffin.

In 1873 the family first appeared in the Indianapolis City Directory. The Howards first lived in a very small frame home at 41 Beeler Street near the Indianapolis Cabinet Company, a neighborhood that today sits under Interstate-70 just east of the Monon Trail. Beverly Howard died in March, 1881, when he was probably about 51 years old. His oldest son Robert continued to live with his mother Catherine on Beeler Street, and in about 1882 Robert began to work as a porter for Indianapolis photographer Albert Fearnaught. Fearnaught conducted a typical family photography firm, but he became best known as the inventor of a grave signal device. Patented in July, 1882, Fearnaught’s device ventilated the casket, and if the victim was interred without actually expiring the prematurely departed would pull a cable releasing a brightly covered flag signaling that the victim should be disinterred. His former porter Robert Howard worked as a photographer under his own name for about a year in 1891, but he would be a janitor or service laborer for the remainder of his working life.

In 1887 Robert Howard married Sarah Dean. Dean’s father Harrison Dean moved to Indianapolis from Kentucky in about 1865, when he was living on Hosbrook Avenue, almost certainly with his wife Melvina and four children including Sarah. The Deans moved to a farm in Clay Township outside Indianapolis in 1870, where they remained into the 1880s. In the late 1890s Robert and Sarah moved to 1012 East 19th Street, which is today an empty lot that sits immediately alongside the Monon Trail’s eastern side.

Sarah became involved in various progressive social organizations, and women’s service groups met at her home including the Progressive Club, the Willing Workers, and the Worthy Matrons Counsel of Calanthe. In May, 1910 she was appointed as an officer on an Alpha Home Association committee, and she remained active in Alpha Home for the remainder of her life. The Alpha Home Board met at the Howards’ East 19th Street home in August, 1910, 1912, and 1913.

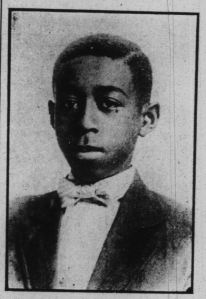

John Wesley Hardrick was featured in the Indianapolis Recorder in 1911 after winning several prizes at the Indiana State Fair.

In July, 1914 Robert and Sarah’s daughter Georgia married John Wesley Hardrick, who would become one of Indiana’s most famous 20th-century artists. Born in Indianapolis in 1891, Hardrick studied with Otto Stark and while a student of Stark’s at Manual Training High School Hardrick probably was the first African-American to study at the John Herron Art Institute in 1907. Hardrick probably first exhibited at the State Fair art exhibition in 1908, and in 1911 the Indianapolis Recorder reported after the State Fair exhibition that “the success of John W. Hardrick is indeed gratifying as well as commendatory. Young Hardrick …. last year entered the John Herron Art lnstitute, where he is now studying oil paintings. This is the fourth year that his work has been on exhibition at the State Fair and each year he has been awarded prizes.”

Madam CJ Walker was one of Hardrick’s most prominent boosters, and she commissioned Hardrick in 1914 to produce a portrait of YMCA President George L. Knox, which she gifted the YMCA. Hardrick simultaneously produced a painting of Madam Walker that he gave her. Hardrick and fellow Indianapolis African-American artist William Edouard Scott were included in the “Tenth Annual Exhibition of Works by Indiana Artists” at Herron in 1917.

Possibly John Wesley Hardrick’s most famous painting, “Little Brown Girl” was executed in 1927 and presented to the John Herron Art Institute two years later.

Perhaps Hardrick’s most famous painting was “Little Brown Girl,” which received the Harmon Foundation Bronze Medal in 1927. The painting depicting an 11-year-old Allen Chapel choir member was gifted to the John Herron Art Institute by a circle of local African Americans two years later. The Herron Art Institute (now known as the Indianapolis Museum of Art) lost the Hardrick painting for more than a half-century until it was found in a private collection in 2003 and eventually re-acquired by the Museum.

Despite his prominence in art circles, Hardrick was unable to sustain a livelihood painting. In 1927 the Indianapolis Recorder alluded to his challenges when it reported on “a commendable exhibit of his paintings at the Pettis Dry Goods Store last week. If you saw it you saw what persistency can do. Hardrick works at odd jobs, supports a wife and four children, but still finds time to paint. He tells us he loves to paint, hopes to be successful. We believe he will for he knows the art of `sticking.’” Hardrick was championed as the “senior colored artist of the Hoosier state” in 1929, but he did indeed work with his family’s moving company and he later managed a carpet cleaning business. Hardrick died in Indianapolis in 1968.

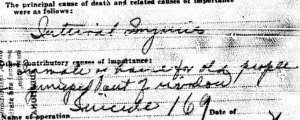

Robert Howard’s March, 1938 death certificate concluded that his fall from an Alpha Home second floor window was intentional, and the coroner ruled it a suicide.

Hardrick’s father-in-law Robert Howard became a widower when his wife Sarah died in 1919. Robert Howard moved near his brother Beverly on Martindale Avenue and worked as a janitor in a scatter of local workplaces. In 1932 Howard moved into the Alpha Home, his entrance perhaps influenced by his wife’s long-term work on behalf of the Home. Howard quietly lived out his remaining years in the home before meeting with Anna Pritchett in January, 1938. Pritchett characterized Howard as “a very kind old man.” Two months later, Howard died of internal injuries from a fall on March 13, 1938. His daughter Georgia Hardrick provided her father’s biographical details for the death certificate. In an unusual and potentially tragic exclamation to Howard’s life, the Coroner decreed that Howard had jumped from the home’s window to his death and ruled it a suicide.

In 1965 the Boulevard Place Alpha Home still had 14 residents and continued with the same mission Eliza Goff had outlined nearly a century earlier. In 1968 Alpha Home received a grant to design a new facility a block north of its long-term location on Boulevard Place (sometimes referred to as North Senate). A year later the Alpha Home confirmed its ambition to build a new Alpha Home, and the move seemed especially well-timed: in June, 1970 the Boulevard Place facility a block away was one of three Indianapolis nursing homes denied a license because of fire hazards. A cornerstore was laid for a new Alpha Home at 1910 North Senate in December, 1970 and it opened a year later. In 1974, 44 residents were living at the facility.

The new Alpha Home was surrounded by the mushrooming Methodist Hospital and lay directly alongside the interstate, and in 1972 the Alpha Home moved to its present location on Cold Springs Road. The Alpha Home continues to operate at that Cold Springs Road facility today, and it continues to uphold many of the same commitments to elder care that it originally championed for African-American elders who had lived through the trauma of captivity.

Image

“Little Brown Girl” John Wesley Hardrick 1927 image from Indianapolis Museum of Art

Pingback: Landscapes of Freedom: Indianapolis Residents in the WPA Slave Narratives | Invisible Indianapolis

Pingback: Indianapolis’ Ahmadi Muslims in the 1920s and 1930s | Invisible Indianapolis

Pingback: Ahmadiyya in Indianapolis – ahmadiyyafactcheckblog