In February 1961 Indianapolis, Indiana’s Jewish Community Center held a public discussion panel on “The Negro as Suburban Neighbor.” The surrounding northside community was home to several of the city’s earliest African-American suburbs, but many of those neighborhoods were resistant to integration. Despite its open membership policy, the JCC also did not count a single African American among its members.

Dr. Reginald Bruce was among the guests asked to speak on behalf of the northwestern suburbs’ African-American residents. In November, 1960 Reginald and Mary Bruce reached an agreement to purchase a home at 5752 Grandiose Drive. The Bruces were the first to integrate the newly built homes along Grandiose Drive. Bruce told the group at the JCC that since moving to Grandiose Drive “his family has been harassed by threatening phone calls and gunshots through the window since moving into the predominately white area.” Some White audience members vigorously opposed integration of the neighborhood, and one complained that the meeting had been rigged by the NAACP.

The Bruces’ experience integrating the northwestern Indianapolis suburbs would be repeated all over the country. That story of suburban integration—long acknowledged in African-American experience but unrecognized by most White suburbanites–is beginning to be told in popular cultural narratives. The suburbs have long been a staple of mainstream cinema, variously painted as disabling assimilation (The Stepford Wives), emotional repression (American Beauty), creative boredom (Grosse Point Blank), profound sadness (The Virgin Suicides), or the prosaic magnet for inexplicable phenomena (Poltergeist, Coneheads, Edward Scissorhands, etc). However, the story of suburban segregation has rarely been told in films.

Last weekend Suburbicon debuted at the Venice Film Festival, and George Clooney’s movie (which opens in the US in October) is distinguished by its ambition to tell the story of racism and integration in suburbia. The film takes its inspiration from the integration of Levittown, Pennsylvania, one of William Levitt’s seven suburban communities. The Levittowns were the model for interchangeable, assembly-line produced housing on the urban periphery, so they are often rhetorical foils for suburban narratives in popular culture and historiography alike. The most unsettling implications of Clooney’s film are that it is an utterly commonplace historical tale: the story of the integration of the Levittown outside Philadelphia in 1957 could be told in any American community.

William Levitt purchased property in the Philadelphia suburbs in 1951, and by 1958 the firm he had inherited from his father had built 17,311 homes. Abraham Levitt and his sons William and Alfred built their first suburban community on Long Island between 1947 and 1951, eventually constructing 17,447 homes there. Levittown homes had racially restrictive covenants that decreed home owners could not rent or sell to Blacks, so the Long Island Levittown may well have been the largest White segregated community on the face of the planet. Postwar suburban housing was made possible by Federal Housing Authority loan programs and a dense network of local codes and informal practices that explicitly segregated the suburban frontier, including the Levittowns. A 1948 Supreme Court ruling found covenants in places like Levittown illegal, and nearly all other segregation practices also became illegal in the next decade (there is a massive scholarship on Levittowns and race and segregation in the Levitt suburbs—compare Herbert Gans’ 1967 The Levittowners: Ways of Life and Politics in a New Suburban Community, Dianne Harris’ edited volume Second Suburb: Levittown, Pennsylvania or David Kushner’s Levittown: Two Families, One Tycoon, and the Fight for Civil Rights in America’s Legendary Suburb).

Nevertheless, William Levitt resisted court-ordered integration, arguing that Whites would not agree to live in integrated communities. In August 1954 Levitt’s most famous comment on the integration of Levittown communities came to the Saturday Evening Post. Levitt explained that “The negroes in America are trying to do in four hundred years what the Jews have not accomplished in six thousand. As a Jew, I have no room in my mind or heart for racial prejudice. But, by various means, I have come to know that if we sell one house to a Negro family, then ninety to ninety-five percent of our white customers will not buy into the community. That is their attitude not ours. We did not create it, and cannot cure it. As a company, our position is simply this: we can solve a housing problem, or we can solve a racial problem. But we cannot combine the two.” Levitt was perhaps not especially committed to segregation, instead blaming xenophobia on his White tenants. When the Post reporter intoned that integration was inevitable, Levitt responded that “If that should happen, there is nothing I can, or would, do about it.”

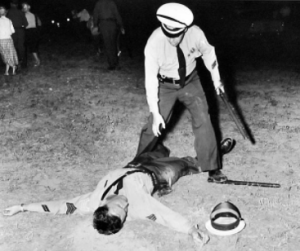

When the Myers moved into Levittown they required police protection, and this officer was injured during one of the vigils (Getty Images).

Suburbicon adapts the story of William and Daisy Myers, who broke the color barrier in the Philadelphia suburban Levittown. In 1957 a Jewish couple sold their property in the Pennsylvania Levittown to the Myers. Neighbors immediately began a campaign to displace the Myers spearheaded by a group calling itself the Levittown Betterment Committee who organized curbside vigils at the home, displayed Confederate flags, threw stones through the Myers’ windows, painted “KKK” on a neighbor’s house, and burnt a cross in a nearby yard (compare the fascinating 1957 documentary “Crisis in Levittown”).

The Myers’ story was certainly enormously public, but it was in many ways a commonplace experience repeated in numerous other American communities. Indianapolis, Indiana had African-American suburbs emerge in the city’s northwestside in the postwar period, but when African Americans moved into White neighborhoods their arrival was greeted with resistance and even violence. For instance, Reginald Alexander Bruce was born in Indianapolis in March, 1925 to Charles and Agnes Bruce. Charles Bruce had come to Indianapolis with his wife Virginia around 1902 from Cedarville, Ohio. Charles married Virginia in 1898, and he married Agnes Smith in April, 1917. Charles and Agnes’ son Reginald was born in the midst of one of the city’s most systematic embraces of xenophobia. In 1926, Indianapolis passed a racial zoning ordinance backed by the White People’s Protective League, and when that was declared unconstitutional neighborhoods like that around Butler University resolved to bar African Americans by other means. Perhaps the most famous impact of 1920s segregation in the Circle City was the creation of a segregated Black high school, and Reginald graduated from Crispus Attucks High School in 1942.

Reginald Bruce had been in ROTC at Attucks, and in March 1944 he completed nine weeks of primary flight training with the 66th Army Air Force at Moton Field. The Alabama airfield was the base for the African-American pilots who became collectively known as the Tuskegee Airmen. In August 1944 Bruce graduated from flight training as part of a class of 14 men trained to fly twin-engine aircraft (medium bombers). Bruce was sent to Douglas Air Field in Arizona, where he was a Flight Officer on B-25s. Bruce was one of 14 Tuskegee Airmen from Indianapolis (see Tuskegee Airmen Indianapolis Chapter word file), and the local pilots including Reginald Bruce would be part of public discussions of the airmen’s legacy into the 1970s. Arthur Carter, the last of the 14 Indianapolis Tuskegee Airmen, died in 2015.

Reginald married Aurelia Jane Stuart in Marion County in 1945, and in 1947 Reginald and his wife were living with Reginald’s parents on Edgemont Avenue. Reginald was a student, and in 1952 Bruce completed his medical training at Indiana University. The young doctor became the resident physician at the Muscatuck State School in 1953, and after a year at Muscatuck Bruce opened a general practice in Indianapolis in July 1954.

After separating from his wife, Reginald remarried and he and his wife Mary attempted to purchase a new home. Apparently their first effort in about 1958 met with failure when “the couple all but succeeded in purchasing a home in the first block east of Butler University on Blue Ridge Road. That was before any Negro had moved onto Blue Ridge. (The first block is still all-white.) In that case, the deal fell through when the seller learned of the Bruces’ racial composition as the check was going through the bank.” In 1960 they successfully purchased the Grandiose Drive home, and despite the harassment and violence directed at the family they remained there until 1967. Perhaps influenced by his own experience of housing discrimination, in January 1961 Reginald Bruce became the co-Chair of the NAACP Indianapolis chapter’s Housing Committee with the Jewish Community Center’s Irving Levine.

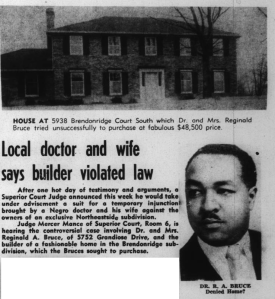

In March 1966 the Indianapolis Recorder reported on Reginald and Mary Bruce’s effort to purchase a home on the northeastside.

The Bruces’ experience of housing discrimination did not end with their experiences on Blue Ridge Road and Grandiose Drive. In January 1966 the Bruces put their Grandiose Drive home up for sale in anticipation of a move into another northern Indianapolis suburb. The builders of a northeastside home on Brendonridge Court, John E. and James P. Dugan, were offered the sale price for the home by the Bruce’s real estate agent, and the Dugans accepted $1000 as a down payment. However, the following day the Dugans informed the Bruces’ agent that the home had been sold, apparently when they realized Reginald Bruce was African American (his wife was White). Mary and Reginald Bruce filed a complaint with the Indiana Civil Rights Commission against John E. Dugan, and in March, 1966 a Marion County Judge granted an injunction against the Dugans preventing them from selling the home until a court hearing. John Dugan filed a counter-complaint seeking $20,000 in damages. The Bruces dropped the charges in June, 1966, and a month later the Grandiose Drive home was on the market heralding the home’s fallout shelter, intercom system, and paneled family room. In 1967 the Bruces had moved to a home on North Illinois Street.

After 19 years in private practice, Reginald Bruce began a radiology residency in August 1973. After divorcing Mary Bruce, Reginald remarried Carolyn Marie Corrington in 1976. Bruce moved to Mattoon, Illinois by the late 1980s, then to the St. Louis suburb of Alton, Illinois, and he finally moved from there to Lake Havasu City Arizona in 1995, where he died in 1997.

The Jewish Community Center did not have a single African-American member when Bruce spoke about his effort to secure housing in 1961. When an audience member spoke out against integration, Joseph Tobak rose and said that “’You say, I like Negroes, but.’ I heard the same thing in Poland 40 years ago—‘We like Jews, but.’ Then came Hitler and his mass murders.” Tobak had indeed left Poland in 1921, eventually opening a liquor store in 1938 on the predominately African-American Northwestern Street, and Tobak’s store did not close until he retired in 1970. We do not know how Reginald Bruce felt about his lifelong experience attempting to secure a measure of equality, but in the wake of that 1961 meeting the JCC did indeed begin to integrate, and much of the northwestside would become home to more African Americans. Perhaps the acknowledgement of Reginald Bruce and William and Daisy Myers stories can start discussions about the depth of such racism and its impact on the contemporary housing landscape.

Sources

David B. Bittan

1958 Ordeal in Levittown. Look 19 August.

Charles E. Frances

2008 The Tuskegee Airmen: The Men who Changed a Nation. Branden Books, Boston.

Herbert Gans

1967 The Levittowners: Ways of Life and Politics in a New Suburban Community. Columbia University Press, New York.

Dianne Harris, editor

2010 Second Suburb: Levittown, Pennsylvania. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh Pennsylvania.

David Kushner

2009 Levittown: Two Families, One Tycoon, and the Fight for Civil Rights in America’s Legendary Suburb. Walker and Company, New York.

Life

1957 Integration Troubles Beset Northern Town. 2 September 43(10): 43-44, 46.

Craig Thompson

1954 Growing Pains of a Brand-New City. Saturday Evening Post 227 (6): 26-27, 71-72. (subscription access)

James J. Wyatt

2012 Covering Suburbia: Newspapers, Suburbanization, and Social Change in the Postwar Philadelphia Region, 1945-1982. PhD Dissertation, Temple University.

Images

House for sale, circa 1955 image from Getty Images

Officer Down Levittown 1957 image from Getty Images

Levittown New York 1947 Drive Carefully sign image from Getty Images

Reginald Bruce Crispus Attucks yearbook 1942 image from Crispus Attucks Museum

William Levitt reads ticker tape 1963 image from Getty Images

Pingback: Color and Conformity: Race and Integration in the Suburbs | Archaeology and Material Culture

Pingback: Color and Conformity: Race and Integration in the Suburbs – The Ties That Bind