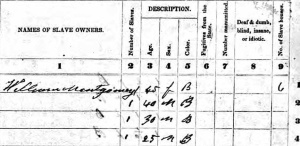

The 1860 Census Slave Schedule inventory of William Montgomery’s captives included the 25-year-old man on line four who was about the age of Green Montgomery (click for a larger image).

On August 13, 1867 Green Montgomery swore an oath of allegiance to the United States, which made him eligible to vote in Floyd County, Georgia. Montgomery had been enslaved in Floyd County, probably since his birth around 1836, and his ascent from property to voting citizen was repeated scores of times throughout the South. Numerous Indianapolis families traced their roots to ancestors like Green and his wife Adaline, who may only have been distinguished by their famous descendant, great-grandson John Leslie “Wes” Montgomery. Wes Montgomery was among the 20th century’s most prominent jazz musicians, but of course the story of Montgomery and his fellow performers reaches beyond music alone, and much of Wes Montgomery’s story mirrors familiar African-American migration patterns, employment inequalities, and urban displacement. Inevitably Wes Montgomery’s biography revolves around music, but it is impossible to understand African-American expressive culture without examining the history of families like the Montgomerys.

Above: The Montgomery brothers (from left, Wes, Monk, and Buddy) circa 1962 (Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images).

In 1860 William Montgomery owned 40 captives housed in six structures on his Floyd County plantation, and one was a 25-year-old man who was quite likely Green Montgomery. Born in South Carolina in 1783, William Montgomery moved to Georgia in the early 1830s, and in 1840 he was living in Floyd County and holding 27 captives. Green Montgomery was one of those slaves at the time Emancipation arrived, if he had not been Montgomery’s captive since birth. Like many newly freed captives, Green initially continued to farm alongside his former owner. Wes Montgomery’s ancestors on his mother’s side were also farmers in northwest Georgia in the post-Civil War period, and they would all follow a common pattern of moving first to regional urban centers and eventually migrating north.

In 1900 Wes Montgomery’s parents Thomas Montgomery and Eufala Blackman (who went by Frances) were living about 16 miles apart in Cave Spring and Rome Georgia, respectively. Thomas appeared in the 1900 census as a 10-year-old, though various primary records recorded his birth year as anywhere between 1887 and 1894; Frances was just a year removed from her birth in March, 1899. Frances’ widowed mother Henrietta, three sisters, and a brother moved to the county seat of Rome by 1900, where Green Montgomery and his wife Anna were living at 27 Wimpee Street by 1910; Thomas Montgomery and his father Craig were living on Freeman’s Ferry Road in 1910 and moved to 201 Hardy Avenue Rome sometime between 1913 and 1916. In 1916 Henrietta Blackman and her daughter were living at 20 Wimpee Street, just a few doors away from Green Montgomery.

In about 1917 Wes’ father Thomas was probably the first of his family and future in-laws to migrate to Indianapolis. It is unclear specifically why Thomas went to Indianapolis, but he may have gone for labor opportunities in the Haughville neighborhood on the city’s west side. He secured work on the eve of the war at National Malleable and Steel Casting, one of several Haughville ironworks. In June, 1882 a company owning ironworks in Cleveland and Chicago purchased Indianapolis’ Johnson Malleable Iron Company (incorporated in 1880) and renamed it Indianapolis Malleable Iron Company, subsequently incorporating in 1890 as National Malleable and Steel Casting Company.

The Haughville factory employed a broad range of White Hoosiers, European immigrants (especially Slovenians), and African Americans until its closing in 1962, but it had a history of color line tensions. In October, 1901, for instance, a circle of White laborers in the factory went on strike against continued employment of Black laborers after the death of a White laborer was blamed on an African American. The Indianapolis News suggested that “racial prejudice has been apparent at the plant for some time,” concluding that existing tension had been amplified by the shooting. On November 8th the White strikers abandoned their cause and returned to the Haughville factory, and the assailant was found guilty and received a life sentence at trial at the end of November. A year later the Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette reported on a “race riot” in Haughville between “200 negroes and whites employed by the National Malleable Casting Co. There has been bitter race feeling between them for several years and trouble has frequently broken out.”

Thomas Montgomery first settled at 1030 North Traub Avenue before he was drafted, and he served from April to July, 1918 in Kentucky. Frances’ mother Henrietta was living just down the street at 1054 North Traub in 1918, and her brother Frank was working in the foundry. Frances must have joined them, because on March 8, 1919 she and Thomas were married in Indianapolis. The newlyweds were living on 1002 North Pershing Avenue on the near-Westside in 1920, and after his military service Thomas returned to work just blocks away at Malleable Castings; his second son William Howard’s 1921 birth certificate identified his occupation as “ash shoveler.” They would move to 1116 North Miley in 1925. The couple’s first child Thomas Montgomery Jr. was born in January, 1920, followed by William Howard (“Monk”) in October, 1921; John Leslie (“Wes”) in March, 1923; Charity Frances in June 1925 (she would die in infancy); Ervena Marie in August, 1927; and Charles (“Buddy”) in 1930.

The first evidence of the Montgomery household’s musicality came in 1926, when the Indianapolis Recorder’s Malleable Castings news column noted that “The Blackburn Quartette met at the home of Tom Montgomery Saturday night for rehearsal. The quartet is making a specialty of folk songs.” The composition of the group is unknown, but it may have been led by an Indianapolis musician named Maurice Blackburn, who lived on West 12th Street in 1926; Blackburn moved to Chicago in about 1928, where he played before moving to Grand Rapids, Michigan, where he was playing in an orchestra in 1930.

Much of the lore that Wes Montgomery and his brothers were untutored musicians risks ignoring the ways music shaped the siblings’ childhood. In 1997 Buddy Montgomery was interviewed by Ted Panken and remembered that “there was music in my soul from the time I was born. My folks weren’t musicians, but they were singers and…you know, they were church people. When I say `music in my soul,’ that’s what I meant, because there has always been music in my family.” Wes Montgomery histories often suggest that Montgomery simply picked up a guitar in about 1943 for the first time, and that was indeed his introduction to electric guitar, but Wes had been given a four-string tenor guitar (probably by his brother Monk) and was playing it as early as 1934 or 1935. Wes Montgomery himself contributed to this image, saying in 1963 that “I can’t read music, I never studied music. Technically I don’t know what I’m doing. You know, I never took guitar lessons. I never was taught how to play the instrument. I just picked it up by listening to records and then figuring things out by myself.”

The Montgomerys were living on North Miley Street in April, 1930 when the census keeper visited, and the neighborhood was universally Black. Most of the neighboring men were working in a foundry, and like Thomas Montgomery it was in most cases certainly Malleable Castings; the remainder were likewise in factory labor (e.g., one neighbor was a “hog killer” in the Kingan and Company Pork and Beef Packers plant).

The Montgomery’s youngest son and last child Charles (“Buddy”) was just two months old when the census keeper visited, but within the next year Thomas and Frances separated. In 1931, Frances was living with her mother Henrietta Blackman at 1050 North Sheffield, which was in Haughville only a few blocks from the Montgomerys’ former home on Miley Street. Ervena Marie Montgomery was living with her mother and brother Buddy through the 1930s and 1940s, when they lived at several different addresses in Haughville. Frances married a foundry worker, Lavester Arrington, in October, 1939.

After separating from his wife Thomas Montgomery moved to Columbus, Ohio, where he first appeared in the city directory in 1932 living at 186 St. Clair Avenue, and he was accompanied by his three oldest sons Thomas Jr., William (Monk), and John (Wes). The boys’ father Thomas Sr. worked into the mid-1950s as a truck driver for a local produce firm. Wes’ grandmother Henrietta (that is, Frances’ mother) died in Indianapolis in 1938, and his oldest brother Thomas died in about 1939. When the census taker came to Thomas Montgomery’s home at 497 Grove Street in Columbus in 1940, Monk was a salesman in a coal yard who was recorded as having completed eight grade; Wes was in school and had completed seventh grade.

Wes Montgomery was recorded by a Columbus census enumerator on April 10, 1940, and he returned to Indianapolis afterward in 1940, where he was almost certainly living with his mother. In 1943 the Indianapolis city directory included a John W. Montgomery living at 1102 North Pershing—probably the initial W was for Wes, since this was the same address as Wes’ mother and her husband Lavester Arrington—and Wes was working at Enterprise Iron and Fence Company, an East 24th Street foundry established in 1883.

In 1950 Wes and Serene Montgomery, his mother Frances and her husband Lavester, and Wes’ sister Lavena and his brother Buddy were all living at 1217 Cornell Street (at the black arrow).

In February 1943 Wes married Serene Miles, who was born in Canton Mississippi in about 1924. Serene and her parents had moved to Indianapolis from Mississippi in 1939, and in 1940 they were living at 320 Blake Street. Wes and Serene first moved in with Frances and Lavester Arrington in Haughville, and they moved to the east side on 1217 Cornell Street in about 1946 (now under the North Split “mixing bowl” interchange of Interstates 65 and 70). Wes’ sister Ervena was living at Cornell Avenue when she graduated from Crispus Attucks High School in 1947. The two-story home at 1217 Cornell was subdivided, and Wes, Serene, and their children were sometimes listed as living in 1217 ½ Cornell Street. The Arrington and Montgomery home backed onto the railway lines for the Chicago, Indianapolis, and Louisville Railway (also known as the Monon Railroad) in an area of modest residential homes alongside scattered warehouses and coal and lumber yards using the railroad connection. In 1947 Wes Montgomery was sharing a home with Frances Arrington at 1217 ½ Cornell Street. Buddy and Ervena were also sharing the home with Wes’ family, their mother, and Lavester Arrington, who was working at National Malleable. Frances Arrington was living at 1217 Cornell Street when she died in May, 1950.

Wes Montgomery said in 1961 that he took up guitar when he was 19 years old, saying he first began to play six-string electric guitar “right after I got married” (i.e., February 1943). In 1967 he remembered that “I was 19, had just gotten married and was working as a welder in Indianapolis when I decided to buy a guitar.” Montgomery was largely a self-taught guitarist, but he later indicated that “there was a cat in Indianapolis named Alex Stevens [sic]. He played guitar, and he was about the toughest cat I heard around our vicinity, and I tried to get him to show me a few things.” That was Alec C. Stephens, who was born in Indianapolis in 1922 and played the celebrated Sunset Terrace in March 1940. He performed in Florida for much of the 1950s and was still playing at his death in 1988.

On July 22, 1944 Ruby Shelton’s newly opened 440 Club advertised for local talent, and Wes Montgomery was one of the local musicians who subsequently performed at the club.

Wes Montgomery’s first public performances came at the 440 Club at 440 Indiana Avenue. Montgomery remembered in a 1961 interview that he began playing solos by Charlie Christian around 1943, and “about six or eight months after I started playing I had taken all the solos off the record and got a job in a club just playing them. I’d play Charlie Christian’s solos, then lay out. Then a cat heard me and hired me for the Club 440.” That cat may have been Millard (Mel) Lee, who led the 440 Club band; however, it also could have been Ruby Shelton, who managed the 440 Club, or Toots Hoy, who played at the club and did much of the 440 Club booking. Ruben Byron “Ruby” Shelton was a fixture of the Avenue landscape, a ragtime pianist, vaudeville performer, and club manager for 60 years. Born in Indianapolis in 1879, Shelton began to play with the Tennessee Warblers traveling show by 1892 and partnered with Indianapolis’ Harry Fidler around 1907, with The San Francisco Call concluding in 1912 that “of all the colored comedians appearing in vaudeville, Harry Fidler and Byron Shelton are the most original and popular.”

In June, 1944 Shelton opened the 440 Club with Palmer Richardson, for whom Shelton managed the P and P Club (i.e., Popularity and Pleasure). A month after his 440 Club opened Shelton began advertising in The Indianapolis Recorder, indicating “talent wanted” for the Club; Montgomery probably played Shelton’s club sometime in summer 1944. Montgomery was playing with some local bands very soon afterward. In August 1950 the Indianapolis Recorder noted that at the outset of his career “Wes played with the Four Kings and A. Jack.” In September 1944 Four Kings and a Jack played a show at the Camp Atterbury military base south of Indianapolis, and the band included “Carl Maynard, Jack Bridges, Emerson Senora, Wm. Cox and Wesley Montgomery.” In November 1944 the band played the Rhumboogie club at 536 ½ Indiana Avenue, and an advertisement for the band’s show has a band picture that may include Wes Montgomery. Montgomery subsequently was playing a host of other clubs such as the Ritz, where he met Jimmy Coe in 1945. The Ritz opened in 1944 at the corner of Indiana and Senate Avenues until it moved to 2648 North Harding Street in November 1957.

On January 5, 1946 The Indianapolis Recorder contained this ad for William Benbow’s “All-American Brownskin Models,” who toured with Millard Lee’s band, which probably included Wes Montgomery.

Montgomery told DownBeat’s Ralph Gleason in 1961 that he first toured with the Brownskin Models and then Snookum Russell. Various versions of the Brownskin Models Revue had been touring since 1925 as a musical troupe featuring dancing, comedy, music, and beautiful African-American women. The Brownskin Models appeared at Indianapolis’ Tomlinson Hall in September, 1945, but Indianapolis vaudeville veteran William Benbow launched his own version of the “All American Brownskin Models” show beginning in January, 1946. It seems likely that Montgomery traveled with Benbow’s show, because he told Ralph Gleason in 1961 that he had been playing in Indianapolis with “Mel Lee—he’s the piano player for B.B. King,” and Millard Lee led Benbow’s Brownskin Models band (and did later play with B.B. King). Isaac “Snookum” Russell toured nearly continuously from 1934 onward, often playing Indianapolis venues including the Sunset Terrace, the Indiana Avenue home to the Ferguson Brothers Agency that managed Russell beginning in about 1941. His band appeared at Tomlinson Hall with the King Cole Trio in 1946 and toured in 1946 and 1947, when Montgomery probably played some dates with Russell.

In May 1948 Wes was invited to tour with Lionel Hampton, a tour that would have taken Montgomery through much of the South in Fall 1948, and Wes continued to play with Hampton through 1950. In 1949 the Indianapolis city directory listed Wes as head of household at 1217 ½ Cornell, and he returned from touring with the Hampton band in January, 1950. From about 1951 to 1956 he was working at P.R. Mallory and Company, a battery and electric component producer, where he was a cafeteria worker in 1951 and a “store keeper” in 1954. In 1957-1958 he was working for Indianapolis’ Polk’s Dairy, which was just a few blocks away on 16th Street. In 1959 Wes appeared in the city directory as a musician for the first time.

During the 1950s Montgomery and his brothers played numerous Indianapolis venues ranging from Indiana Avenue clubs to more unconventional performance spaces. In September, 1950, for instance, they and drummer Willis Kirk headlined a Be Bop Society concert at the Phyllis Wheatley YWCA, and in July 1952 they played Central State Hospital. The Indianapolis News’ Charlie Davis reported that the YWCA benefit featured the “Montgomery Quartet, as hot an outfit as these parts have seen in many a moon.” The brothers played with a wide range of different lineups. In November, 1957, for instance, the Indianapolis Recorder reported that the brothers were playing with Alonzo “Pookie” Johnson: “Montgomery Johnson, four all stars, are playing six nites a week at the Tropic Club. Believe it or not, the cats are wailing without a piano, and they really sound good.” Johnson was born in 1927, the son of musician James Dupee, and Pookie honed his craft in the Crispus Attucks music program. Johnson told Lissa Fleming May in 2003 that he first heard Wes Montgomery play in 1944 at the 440 Club, and he would play with the Montgomerys and various other musicians between about 1950 and 1956. Johnson and Monk Montgomery played with drummer Sonny Johnson’s band at the Turf Club in 1954, and the Montgomerys and Johnson played several long engagements at the Turf Club in the late 1950s.

Both Monk and Buddy were accomplished musicians, playing together as well as in other bands throughout the postwar period. Monk Montgomery had played with the Be Bop Society in September, 1948 (a band that included his brother Buddy and Wes’ mentor Alec Stephens) and again in a series of January 1949 “Jazz at the Auditorium” shows. In January 1949 Monk was playing an extended engagement at the Tropic Club at 2039 East 10th Street, where he was apparently one of two Black musicians in the club’s orchestra in August 1952 (In March 1954 Wes would also play the Tropic Club).

Like Wes several years earlier, Monk began to tour with Lionel Hampton beginning in January 1953, and during that tour Monk began to experiment with the electric bass. Monk became famed for being an innovator on the electric bass, but for those with subscription access, Brian F. Wright’s paper on Montgomery and the adoption of the electric bass paints a fascinating picture of Montgomery’s reluctance to begin playing the newly introduced electric bass when he joined Hampton’s band. Hampton’s band may have been playing the Fender Precision Bass as early as December 1951, when an Iowa paper described the band’s “very low pitched bass guitar”; in May 1952 The Pittsburgh Courier reported that “Lionel Hampton, always on the look-see for something new in the way of modern sound, has given a heavier, fuller tone to his tremendous orchestra with the introduction of the Fender Bass, a new electronic instrument destined to replace the popular bass.” The Courier suggested that the “instrument looks like a freakish conception of an electric guitar.” Despite his initial reluctance to adopt the electric bass, in July 1953 Monk became perhaps the first jazz guitarist to record electric bass, playing on four tracks on the Art Farmer Septet album, which was released in 1956. In September 1953 the bass was well-received as Monk traveled with Hampton’s band to Norway and then on to stops including Sweden, the Netherlands, France, and northern Africa before returning in December, 1953.

The youngest Montgomery brother Buddy first toured in 1948 with a band led by Jimmy Coe. Coe graduated from Crispus Attucks in 1938 and met Wes in about 1945. In 1997 Buddy Montgomery recounted that Coe was leading a band in 1948 that had “another Blues piano player, I think, who was scheduled to go, and couldn’t make it, so I was asked to go. … I’d just gotten started; I’d only been playing for about six months or so. But he thought I was good enough to go, so I went, and it was a very enjoyable experience for me. It was down South. My first time.” This likely was the 1948 tour on which Coe accompanied Tiny Bradshaw.

In June, 1954 Duke Ellington played the Turf Bar with Sonny Johnson’s quintette, which included Monk Montgomery and Pookie Johnson in the band.

The brothers played a host of Indianapolis clubs and ventured out of the city into neighboring communities like Muncie (1952). In addition to scattered jam sessions, they played long engagements at some local clubs. In 1955-1957, for instance, Monk appeared in the Indianapolis city directory as “musician Turf Bar,” apparently playing there in a semi-permanent gig while living at 3048 North Kenwood Avenue; in 1957, his brother Buddy was also listed as “musician Turf Bar.” The Turf Bar (sometimes called the Turf Club) at 2320 West 16th Street lay just over the 16th Street bridge into Haughville, a neighborhood that the Montgomerys knew well from their childhood, and by September 1954 the Johnson-Montgomery band was playing the Turf Bar and would remain fixtures through the 1950s.

The Turf Bar began life as the Embassy Restaurant. Fred “Pop” Junemann opened Ye Auto Stop restaurant in August 1919, promising “music at all times,” and in 1925 he opened the Embassy Restaurant a few doors away in the building that would become the Turf Bar. After Junemann’s death in 1934 the Embassy continued to feature musicians and dancing, and it became the Turf Bar in May, 1939. The Turf Bar was primarily a restaurant and saloon that went through a series of owners until it changed ownership in May, 1953 and began once again featuring musicians. In June 1954 the bar featured its first national artists when it hosted the Duke Ellington Orchestra with Sonny Johnson’s band, which included Monk Montgomery, Pookie Johnson, and Gene Fowlkes.

In October 1959 the Indianapolis Recorder noted that “the fabulous Wes Montgomery Trio is currently at the Turf Club nitely,” and in February 1960 Wes was playing the Turf Club when its owner Mildred Thompson was arrested for refusing to seat an African-American party. In March she again refused to admit African-American customers, saying that it was “`because it would hurt our business.’” She told a group seeking entrance to the club that “`We’d prefer not to serve Negroes here: it’s bad for the business’” and argued that “‘Every business has a right to refuse service to whoever it wants.’” On April 9 the Indianapolis Recorder reported that the “management of the Turf Club has made its position unmistakably clear. Already adamant in its refusal to accord equal service to Negro patrons, the management reacted to a weekend picket at the establishment at 16th and Lafayette Road by unfurling a Confederate flag.” By 1960 public accommodations like the Turf Club had been legally integrated, but the club was among the many venues that resisted such law despite featuring African-American artists, and in May, 1960 Thompson was cleared of discrimination charges. However, it appears that Wes Montgomery did not again play the Turf Club (Buddy’s band returned in August 1968, a band that included his brother Monk). The club became a pizza restaurant in September, 1972, and since about 1987 it has been an adult dance club.

Monk formed a band in Indianapolis in 1956, and in December 1956 or January 1957 he, Buddy, and drummer Ben “Benny” Caldwell Barth drove to Seattle, where they were joined by pianist Richard Crabtree for a three-month gig starting January 14, 1957. Buddy’s wife convinced the band to adopt the name the Mastersounds, and they played Washington clubs and then traveled to San Francisco to play the Jazz Showcase club. In 1958 neither Monk nor Buddy appeared in the Indianapolis City Directory, and they would never be permanent residents of Indianapolis again. Their sister Ervena had married George Herman Floyd in May 1957, and in 1958 she was living at 3046 ½ North Kenwood, next door to the home she had shared with her brothers the year before.

After this September 7, 1959 show, Julian “Cannonball” Adderley went to see the show of Wes Montgomery at the Missile Room. Ten days later he urged Riverside Records producer Orrin Keepnews to sign Montgomery.

Wes Montgomery hagiography typically argues that he was discovered at the Missile Room, a West Street club that opened in May 1958. The club at 518 North West Street did indeed feature Montgomery in its first live shows, and in the audience for one of those shows in September 1959 was saxophonist Julian “Cannonball” Adderley. Riverside Records’ producer Orrin Keepnews later confirmed that Adderley met with him in his New York office on September 17, 1959 and urged Keepnews to sign Montgomery. Adderly had played Indianapolis’ Claypool Hotel on September 7th in a show that included George Shearing, Thelonius Monk, and Chet Baker. After shows in Cincinnati September 10th and Chicago September 11th they were back in New York by September 17th, where Keepnews indicated Adderly had told him about Montgomery, so it is likely his memory of being told about Montgomery on September 17th was reasonably accurate. Montgomery’s first Riverside release was The Wes Montgomery Trio, which was recorded in October 1959 and came out before the end of the year.

Embed from Getty ImagesWes Montgomery appeared in this Riverside Records promotional image around 1960 (Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Image).

Keepnews said that on almost the same day Adderley visited him, he read an influential Gunther Schuller article that celebrated Indianapolis jazz in the September 1959 issue of Jazz Review (on pages 48-50 of this PDF). Indianapolis musician David Baker recalled in a 2000 interview that “My big band–1959 we won the Notre Dame Jazz Festival. … Gunther Schuller was in–playing French horn in the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. While he was down here [Bloomington], we entertained them with the big band. He heard me, and he wrote the article–I took him up to hear Wes Montgomery at the Missile Room. That’s when he wrote the article called … ‘Indiana Renaissance.’ It was about my big band and about Wes Montgomery.” Schuller provided an enormously effusive tribute to Montgomery, who he said “is an extraordinarily spectacular guitarist. Listening to his solos is like teetering continually at the edge of a brink. His playing at its peak becomes unbearably exciting, to the point where one feels unable to muster sufficient physical endurance to outlast it.” Baker recounted that “I took him to hear Wes while he was here. He couldn’t believe that. It was Wes Montgomery, Paul Parker, and Melvin Rhyne. They were playing at an after-hours club called the Missile Room, which was right across the street from the Walker Theater–well, right across the street there was a funeral home, and then the next one was the Missile Room.” (The funeral home Baker recalled was the People’s Funeral Home at 526 North West Street).

Montgomery would spend most of his life in Indianapolis, and Schuller lamented that Montgomery and many of his Avenue jazz peers were not especially well-known beyond local circles: “At first thought, it seems a shame for jazz in general, and for those of us who would appreciate his playing, that Wes Montgomery cannot be heard in New York.” However, Schuller quite presciently concluded that “I have a sneaking suspicion that playing in an after-hours place in Indianapolis (as he did the night I heard him) is better for Wes Montgomery and jazz in general than almost anything I can think of. In Indianapolis, a city which evidently no self-respecting name group would deign to visit, there is a real place and need for Wes Montgomery—which, come to think of it, probably accounts to some extent for the fact that he seems to be one of the most well-adjusted, happy musicians I have met in years.”

In February 1960 music critic Charles Hanna celebrated The Wes Montgomery Trio album and indicated that “Most nights he works with organist Melvin Rhyne and drummer Paul Parker in Indianapolis’ Turf club and at the Missile room after hours. Buddy and Monk worked the Turf room with Wes before they went to the west coast several years ago.” By that point in 1960 none of the Montgomery Brothers was living in Indianapolis as their primary residence, and in the Fall of 1960 all three brothers were living in Berkeley California but touring regularly (e.g., their busy 1961 tour schedule included Philadelphia in January 1961, Detroit in February, Pittsburgh in June, Detroit again in August, back in Berkeley in October, and Kansas City in November).

In January 1962 Serene was back in Indianapolis for the birth of a son in Methodist Hospital that was reported in the Indianapolis Recorder on January 20th, and on January 29th the brothers played a show in Syracuse. In March, 1963 the Oakland Tribune reported that Wes was visiting Oakland before “returning to Indianapolis,” and on March 29th he was playing Indianapolis’ Prince Hall Mason’s lodge. While Wes did not appear in the 1963 Indianapolis city directory, Serene was listed as living at 1217 Cornell and working as a packer at the Hygrade meat packing plant. Wes was apparently visiting Indianapolis regularly (e.g., he was playing the Hub Bub Lounge at 124 West 30th Street in August 1963, and Buddy and his own band would play the same club in September), but he was still doing some touring, visiting San Francisco in June, Detroit in November, and Philadelphia in December.

By the time this picture was taken in 1972, all the homes on Cornell Street–and the street itself–had been razed, including the Montgomery’s former home at the red arrow. This is today the “north split” confluence of Interstates 65 and 70.

By the early 1960s plans for an inner-city highway were targeting Cornell Street and many of the surrounding neighborhoods, and in 1964 the home at 1217 Cornell Street was vacant. Wes and Serene Montgomery moved to a home at 641 West 44th Street near Butler University that was listed for sale in the Indianapolis Star in June 1963 as an “American colonial in choice loc overlooking Butler campus.” The home was listed as sold November 24, 1963, and the previous resident had moved out by May 1964, so Wes, Serene, and their seven children probably were in the home in early 1964, if not late 1963. Wes and Serene appeared as residents of the home in the 1965 directory, which listed his occupation as “musician Wes Montgomery Trio.”

After the Montgomerys moved from 1217 Cornell it was never a residence again. By 1967 most of the homes on the street were vacant, and by 1969, only one vacant house was standing in the 1200 block of Cornell Avenue. In 1972 the footprint for the contemporary North Split interchange between I-65 and I-70 had razed all of the streetscape and the homes that once lined Cornell.

Wes was a well-established international star by 1967 and had signed with A&M Records, so he was consistently in the Los Angeles area for recordings and live performances: he played the Hollywood Bowl in July; he performed with Nina Simone and Dick Gregory several nights later at Los Angeles’ Shrine Auditorium; he played for a month beginning August 8th at The Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach, California; and he and his brothers played together at Shelly’s Manne Hole in Hollywood in October. Yet Montgomery continued to spend time in Indianapolis and perform locally, including a May 1967 show with Cannonball Adderley at the Murat Theatre, and a November 1967 performance with Addereley at Butler University’s Clowes Hall, just blocks from the Montgomery home on West 44th Street.

Montgomery was touring at the start of 1968, playing in Minneapolis and New York City in January, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh in February; Cincinnati, Gary Indiana, Milwaukee, and Los Angeles in March; Philadelphia and Kansas City in April; Philadelphia and Chicago in May; Anaheim May 28th-June 2nd; and Phoenix on June 3-5. The Phoenix show at Caesar’s Forum would be his last public performance. Montgomery returned home to Indianapolis in preparation for a busy summer in which he was scheduled to play the Pittsburgh Jazz Festival on June 23 and then the Hampton Virginia Jazz Festival June 27-29.

Montgomery was at his home on West 44th Street on June 15 when he woke up feeling ill and collapsed after a heart attack, and at 10:40 AM he was pronounced dead at Methodist Hospital. Montgomery’s funeral service was in Puritan Baptist Church. Puritan Baptist Church was founded in 1944 at 2611 Annette Street, they had moved just a few doors away to 945 Roache Street by 1951, and in 1968 they were worshipping a block from their original location at 872 West 27th Street. Montgomery’s brothers Monk and Buddy were among the pallbearers as Wes Montgomery’s casket was taken to New Crown Cemetery. Montgomery’s father Thomas had been buried there in 1956. Monk and Buddy remained active performers for decades after the death of their 45-year-old brother. Monk died in May 1982 and is buried in Las Vegas. Buddy moved to Milwaukee after Wes’ death and then back to California in the 1980s, where he died in May 2009 in Palmdale, California.

In the absence of much surviving historical architecture, musical landscapes have often figured as rather anonymous backdrops, and much of the city Wes Montgomery knew is today radically different than it was just a half century ago. Nevertheless, the broad range of Indianapolis’ music places Montgomery and his peers knew still has a story to be told and even preserved on the contemporary landscape.

Embed from Getty ImagesAbove: Wes Montgomery performs with his brothers Monk and Buddy at the Five Spot nightclub , New York City January 23, 1961

Sources

Elspeth H. Brown

2014 The Commodification of Aesthetic Feeling: Race, Sexuality, and the 1920s Stage Model. Feminist Studies 40(1): 65-97.

Reno De Stefano

1996 Wes Montgomery’s improvisational style (1959-1963): The Riverside years. PhD Dissertation, Universite de Montreal.

Preston Lauterbach

2011 The Chitlin’ Circuit and the Road to Rock ‘N’ Roll. W.W. Norton and Company, New York.

Lissa Fleming May

2005 Early Musical Development of Selected African American Jazz Musicians in Indianapolis in the 1930s and 1940s. Journal of Historical Research in Music Education 27(1): 21-32. (subscription access)

Duncan Schiedt

1977 The Jazz State of Indiana. Duncan P. Schiedt, Pittsboro, Indiana.

Shawn Salmon

2011 Imitation, assimilation, and innovation: Charlie Christian’s influence on Wes Montgomery’s improvisational style in his early recordings (1957–1960). PhD Dissertation, Ball State University.

David Leander Williams

2014 Indianapolis Jazz: The Masters, Legends and Legacy of Indiana Avenue. The History Press, Charleston, South Carolina.

Brian F. Wright

2014 “A Bastard Instrument”: The Fender Precision Bass, Monk Montgomery, and Jazz in the 1950s. Jazz Perspectives 8(3): 281–303. (subscription access)

Images

Montgomery Brothers image circa 1962 Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Montgomery Brothers January 1961 performance image by Sam Falk/New York Times Co./Getty Images.

Wes Montgomery Riverside Records promotional image Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Thank you for this wonderfull, enlightening piece about Wes Montgomery, the greatest guitar player of all time.

LikeLike

What an excellent piece of work! It fills many information gaps about Wes’ family and his early childhood. Thank you for all the work you have put into this.

Oliver Dunskus, Author of “Wes Montgomery, sein Leben, seine Musik”, the first Wes Montgomery biography (in German) published in the last 30 years. 300 pages, available on Amazon.

LikeLike

Pingback: Consuming Indiana Avenue: Memory, Marketing, and Jazz Heritage in Indianapolis | Archaeology and Material Culture